Toward a revised checklist of the Western Palearctic butterflies, hyperlinked to the original descriptions at species, genus and family level (Lepidoptera, Papilionoidea)

Part II: Rationale and framework for the Hesperiidae.

Submitted: 11.ix.2025 | Accepted: 22.ix.2025 | Published online: 30.ix.2025.

DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.17152671

IntroductionNomenclatural stability is a cornerstone of taxonomy, providing the consistency required for effective communication in ecological, evolutionary, and conservation research. The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) establishes rules to ensure such stability, yet its application is not always straightforward, especially when historical precedence, prevailing usage, and recent scientific insights diverge.

The butterfly family Hesperiidae exemplifies these challenges. Although its members are relatively well studied in terms of morphology and distribution, their classification has long been complicated by subtle diagnostic features, overlapping variation among species, and a historical accumulation of competing names. Subfamilies and tribes have been redefined repeatedly, while synonymy, priority, and homonymy issues continue to affect genera and species.

The advent of molecular systematics has clarified many relationships but has also revealed cryptic diversity and conflicting interpretations. Limited genetic markers or narrowly focused morphological studies have sometimes produced inconsistent results, underscoring the need for broad genomic analyses and comprehensive morphological surveys that capture the full range of variation.

In this context, a reassessment of Hesperiidae nomenclature in the West Palearctic is timely. By aligning historical literature, ICZN provisions, and modern phylogenetic insights, a more consistent framework can be developed. This framework aims not only to provide stability but also to highlight unresolved cases, pointing to areas where large-scale integrative studies will be necessary for definitive resolution.

1.4. References

Aurivillius C. 1925. 9. Familie: Hesperidae. In: Seitz, Die Gross-Schmetterlinge der Erde 13: 505-588. (url)

Duméril C. 1806. — Zoologie analytique, ou méthode naturelle de classification des animaux, rendue plus facile à l'aide de tableaux synoptiques. Paris: Allais (Ed.). pp. i-xxxiii, 1-344. (url)

Heteropterus Duméril, 1806. Zool. analyt.: 271.)

Hübner J. 1816-[1826]. — Verzeichniss bekannter Schmett[er]linge. Ausburg: bey dem Verfasser (Ed.). pp. 1-431, Anzeiger: 1-72. (url)

Cyclopides Hübner, [1819]. — Verz. Bekannt. Schmett.(7):111. (url)

Speyer A. 1879. Die Hesperiden-Gattungen des europäischen Faunengebiets. II. Nachträge. Das Flügelgeäder. Entomologische Zeitung 40(10-12): 477-500. (url)

Verity R. 1940. Le Farfalle diurne d'Italia. Volume primo, Considerazioni generali e Superfamiglia Hesperides. Firenze: Marzocco SA (Ed.). pp. i-xxxiv, 1-131, pl. 1-4, pl. [morphology] I-II (url p. 86).

Warren A., Ogawa J. & Brower A. 2008. Phylogenetic relationships of subfamilies and circumscription of tribes in the family Hesperiidae (Lepidoptera: Hesperioidea). Cladistics 24(5): 642-676. (url) https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-0031.2008.00218.x

2. Classification of tribes within the subfamily Hesperiinae

Chiba H., Tsukiyama H. & Bozano G. 2025. In: Bozano G. C., Guide to the Butterflies of the Palearctic Region. Hesperiidae part 2, Subfamilies Trapezitinae and Hesperiinae (partim). Milano: Omnes Artes (Ed.). pp. 1-82.

Huang Z., Chiba H., Hu Y., Deng X., Fei W., Sáfián S., Wu L., Wang M. & Fan X. 2024. Molecular phylogeny of Hesperiidae (Lepidoptera) with an emphasis on Asian and African genera. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 198(108119): 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2024.108119

Warren A., Ogawa J. & Brower A. 2009. Revised classification of the family Hesperiidae (Lepidoptera: Hesperioidea) based on combined molecular and morphological data. Systematic Entomology 34(3): 467-523. (url) https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3113.2008.00463.x

3. Agreement in gender and the example of Carterocephalus silvicola

3.1. Taxonomic context and evidence

The introduction to the AWPL checklist explains why species-group names have not been grammatically aligned with their respective genus names, contrary to the recommendation of Article 31.2 of the Code, following the arguments of van Nieuwkerken et al. (2019). The name silvicola provides a clear case where the correct application of the Code requires a strong command of Latin grammar; limited or partial knowledge can easily lead to errors that may compromise nomenclatural stability.

In summary of the ICZN Code, species names (specific epithets) can be of three main types, and gender agreement depends on their type:

1. Qualifying adjectives

For example, albus (masculine), alba (feminine), and album (neuter) all mean “white”, and the form used depends on the grammatical gender of the genus name.

2. Present participles or invariable substantivized adjectives

Certain Latin present participles or substantivized adjectives are invariable in gender, so they remain the same regardless of the gender of the genus.

3. Nouns used as epithets

Example: homo, panthera, rex

Nouns remain invariable, irrespective of the gender of the genus. In such cases, the genus does not affect the spelling of the epithet.

For the epithet silvicola in the genus Carterocephalus:

a) Carterocephalus is masculine.

b) silvicola (“inhabitant of forests”) is a noun in apposition or an invariable participle.

The correct combination is therefore Carterocephalus silvicola.

Nevertheless, several authors (e.g. Henriksen & Kreutzer 1982; Tshikolovets 2011; …) have used silvicolus, either treating silvicola as a feminine adjective or assuming that the endings of the two names (Carterocephalus silvicolus) should be made to agree phonetically.

4. Ochlodes sylvanus (Esper, 1777)

4.1. Taxonomic context and evidence

The name Ochlodes venatus Bremer & Grey, 1852 (original combination: Hesperia venata Bremer & Grey, 1852) was long applied to the only European representative of Ochlodes. However, because this taxon was described after sylvanus Esper, [1777], the latter has priority. In addition, the study of Farahpour-Haghani et al. (2023) demonstrates a substantial genetic divergence between venata and sylvanus, supporting their treatment as distinct species.

5. Subfamily name Pyrginae Burmeister, 1878

5.1. Taxonomic context and evidence

Antigonini Mabille, 1878 is a senior synonym of Pyrgidae Burmeister, 1878, but under ICZN Article 35.5 (Precedence for names in use at higher rank) the precedence of Pyrgidae over Antigonini must be maintained.

6. Classification within the Carcharodini tribe

6.1. Reference classification

The classification of genera, subgenera, and species adopted here follows Zhang et al. (2020) and Zhang et al. (2023). These authors revised the combinations of several species, the main change being the transfer of most species formerly placed in the genus Carcharodus Hübner, [1819], to the Muschampia Tutt, 1906, subgenus Reverdinus Ragusa, 1919.

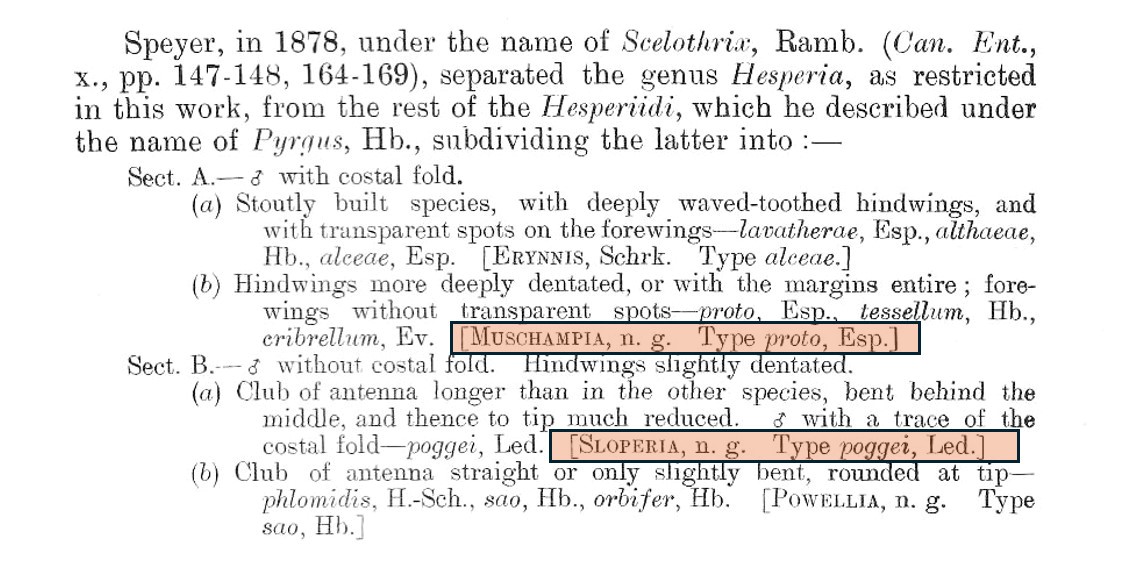

7. Genus Muschampia Tutt, 1906 or Sloperia Tutt, 1906?

7.1. Taxonomic context and evidence

Both names were established on the same page of Tutt’s 1906 publication, with Muschampia appearing before Sloperia. The chronology is unambiguous, as the author described (wrote) the former first, followed by the latter.

Nevertheless, the name Sloperia has continued to be used in recent literature (e.g. García-Barros et al. 2013), as some authors interpret the two names as having been published simultaneously and therefore invoke Article 24 of the Code (‘Precedence between simultaneously published names’). This Article assigns the choice of precedence to the First Reviser, in this case Warren (1926), who in his monograph on this species-group adopted the genus Sloperia.

However, both names are retained at the subgeneric level (see Zhang et al., 2020), with Muschampia applied to the species related to proto Esper, [1808], and Sloperia to those related to poggei Lederer, 1858.

8. Who is the original author of Papilio proto?

8.1. Taxonomic context and evidence

Most recent systematists (Leraut 1997; García-Barros et al. 2013; Wiemers et al. 2018; Dapporto et al. 2023, ...) attribute authorship of the taxon proto to Ochsenheimer, 1808. However, immediately following his Latin description, Ochsenheimer cited Esper’s Schm[etterlinge]. I. Th[eil]. Tab. CXXIII, Cont. 78, f. 5 (mas.), f. 6 (foem.) P. Proto’), indicating that Ochsenheimer was aware of plate 123 of Esper’s work prior to the 1808 publication of the second part of volume 1 of his Die Schmetterlinge von Europa.

Heppner (1982) published a detailed study on the dating of early entomological works. While such publications typically bear a title-page date, they were generally issued in separate fascicles distributed prior to the completed book. Drawing on archival sources and correspondence, Heppner reconstructed the circulation dates of these fascicles, concluding that pages 25–48 and plates 123–126 of the second part of the supplement to the first volume of Esper’s Die Schmetterlinge in Abbildungen nach der Natur… appeared between 1805 and 1830. Although this does not establish the precise date of plate 123, Ochsenheimer’s citation of it in 1808 strongly suggests that the plate was published before or in 1808.

9. The species from the Muschampia proto species group

9.1. Taxonomic context and evidence

The checklist follows the revision of the proto species group by Hinojosa et al. (2021), which revealed overlooked cryptic diversity and demonstrated sufficient divergence to recognize three distinct species in Europe: Muschampia proto in southwestern Europe and North Africa, M. alta in southern Italy and the Balkans, and M. proteides in southeastern Europe (E Ukraine, S Russia) and western Asia.

10. Pyrgus bellieri (Oberthür) or Pyrgus foulquieri (Oberthür)

10.1. Taxonomic context and evidence

Both names were established on the same page of Oberthür’s 1910 publication, with bellieri preceding foulquieri. The chronology is unambiguous, as the former was described first.

However, the name foulquieri has been more frequently used in recent literature (Wiemers et al. 2018; Dapporto et al. 2022, ...), with some authors treating the two names as simultaneously published and invoking Article 24 of the Code (‘Precedence between simultaneously published names’). Under this Article, precedence is determined by the First Reviser, but differing interpretations of who qualifies as First Reviser have resulted in nomenclatural instability.

11. The Pyrgus alveus species group

11.1. Taxonomic context and evidence

Many specialists (e.g., Warren 1926; de Jong 1972, ...) have studied the genus Pyrgus in detail. The examination of male genitalia has often proved decisive in distinguishing between different species.

Three subgenera have also been defined based on the structure of the male genitalia. The recent study by Pitteloud et al. (2017) on the phylogeny of Pyrgus confirms the existence of species groups within the genus that correspond to the subgenera established on the basis of genitalia structure.

Ateleomorpha Warren, 1926, one of these subgenera, still comprises species groups that exhibit only minor differences in genitalia structure. These groups can be summarised as follows: ‘serratulae/carlinae/cirsii ’, ‘cinarae ’, ‘onopordi ’, and a group of species more or less closely related to ‘alveus ’.

However, the various populations of species within the alveus group show considerable variability in the shape of the genital valve. Renner (1991) devoted a highly detailed monograph on this subject and drew several conclusions, some of which have not been supported by subsequent phylogenetic studies.

These more recent studies (Pitteloud et al., 2017; Dapporto et al., 2022, …) indicate that some taxa show sufficient genetic divergence to be considered valid species, while others remain questionable or require further investigation. The presumed species and closely related taxa, whose status remains uncertain at present, include:

- armoricanus Oberthür with sp./ssp./ESU? maroccanus Picard 1948, persica Reverdin 1913 and philonides Hemming

- numidus Oberthür

- jupei Alberti

- bellieri Oberthür with sp./ssp./ESU? foulquieri Oberthür , picena Verity and corsicae Renner

- alveus Hübner with sp./ssp./ESU? accreta Verity , trebevicensis Warren and centralitaliae Verity

- warrenensis Verity

|